The 1920s was a time of fascination and invention. Besides fashion and great music, it gave us Talkies, Transatlantic flight, and refrigerators. Continue reading

The 1920s was a time of fascination and invention. Besides fashion and great music, it gave us Talkies, Transatlantic flight, and refrigerators. Continue reading

There are people who simply look ridiculous in a hat and then there are hat people, people with the right shaped head and hat faces. Continue reading

Happy autumn! Although my school days (daze) are well behind me, September never fails to stir longings for freshly sharpened pencils, a classy pen with a nice grip, new outfits, and books, books and more books.

Another autumn tradition is the return of those who fled the summer city for cooler environs and the beginning of the fall social season. Not everyone thinks of it this way: “Fall Social Season” or “The Season”, especially in these days of nonconformity, but back in the day, during two of my favorite time periods, the turn of the century, i.e. 1880-1900 and the Roaring Twenties, they took their seasons very seriously. What events you attended or missed, how you were perceived or weren’t, could have deadly consequences. And no one chronicled those heady moments as beautifully as Edith Wharton (except perhaps Henry James).

Wharton is one of my favorite writers, so naturally, she is also one of Harlow Ophelia Jackson’s favorite writers. And although there are tendrils of emphatic synergy to be found in Age of Innocence, Custom of the Country, and the short stories of Roman Fever, nowhere is there more of a connection between my main character and Wharton’s main character than in The House of Mirth.

As I write, Wharton’s ability to vividly render her protagonists fears and strengths while never losing sight of a world which shapes and contorts them with a silent pressure, is never far from my mind.

Just as September brings new beginnings and possibilities, Wharton conjures the past and all that women fought through to get here to the present. Wharton’s characters don’t always win, but just like my Harlow Ophelia, they always fight.

So, in the spirit of new seasons, fresh beginnings, and the joy of cracking open new books, but never their spines—school tomes and works of pleasure alike—this month I offer you a brief book review, more like a recommendation. Most likely you have already luxuriated in the heartbreaking joy that is Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. After all, it is 113 years old. But if you haven’t, then please bookmark this blog post and run out to your nearest bookstore or download a copy to your Kindle. Read it and then return to commiserate with a fellow Whartonian (I just made that up. I don’t know what Edith Wharton fans are called, but it sounds good!)

Lily Bart is my muse and one of my greatest fears. Beautiful, brash, foolishly believing she has nothing but time on her hands, she navigates the world as if it has been custom ordered from her favorite dressmaker.

Every couple of years I re-read The House of Mirth, which was published in 1905 by Charles Scribner’s Sons—with several film adaptations to follow—and every time it is a revelation. It breaks my heart and fills me with dread. It’s my personal Frankenstein, especially as I strangely continue to get older with nary a sugar daddy or husband in sight!

Beautiful, smart, possessed of a good family name but little money, Lily assumes when she is ready she will marry well and that will be that. And so do we, enjoying as she bucks conventions, flirts outrageously with the handsome but poor bachelor Lawrence Selden. But we begin to worry as our Lily lets her liking for gambling get the better of her and thoughtlessly endangers her reputation with her lecherous uncle Gus Trenor and the wealthy businessman Mr. Rosedale.

An orphan who tasted the good life before her parent’s death, she has lost neither her love for the finer things nor her grief over abandonment and what life should have been. Her grip on possibilities, alternate endings keep her from settling. Instead, for ten years, she flits from man to man, opportunity to opportunity holding out for something better. Something that will fit the shape of what she has only imagined but never experienced.

But although her imaginings are vital, pulse with life, so does time, which continues to march on as she continues to refuse to make a choice between financial and social stability and freedom.

Selden, in love but knowing his is a lost cause, watches from afar and occasionally tries to caution Lily. She holds genuine affection for him but dismisses his counsel and that of others who warn her that beauty and reputation are fleeting and time swift.

Over the two-year time span of the novel, Lily squanders what little money she has, her priceless reputation, her youth, and her pride. She is left unmarried at the end of the season and banned from polite society. She is devastated and yet unable to make any other choice.

The end of The House of Mirth is still debated one hundred plus years later. I have my staunch opinion about her fate as do others. But whatever camp one falls into, everyone agrees that Lily Bart’s house is founded on a bitter mirth and echoes with tears.

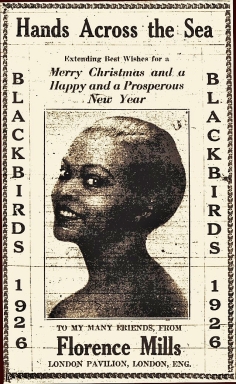

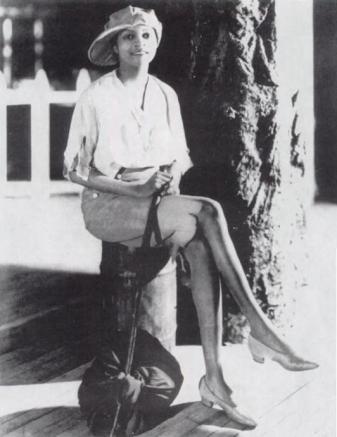

Florence Mills circa 1921

We are here for the briefest of moments. Like shooting stars, we burn bright for a finite amount of time perhaps twenty years, thirty years, two hours, maybe even one hundred years, and then in the blink of the eye, we’re gone.

As an avid student of history, I am fascinated by and marvel at all of the unheard, unknown people who have lived throughout time. More people have come and gone than we can even fathom, their stories lost to the relentless sweep of time or the arbitrary whim of those who keep the records.

As a writer, I am drawn to characters, real and fictional, who readers may not have heard of or imagined gamboling through the world. One of the best things about writing historical fiction is the people I discover as I research my books. Cabaret singer, dancer, and comedian Florence Mills is one of the fascinating women I came across in 2013 as I began to conjure the world of the Harlow Ophelia Jackson mystery series. Charmed by the fetching Washington DC native’s renaissance career which parallels my main character’s, I promptly made her one of Harlow’s ride-or-die besties.

The Mills Sisters

Born Florence Winfrey on January 25, 1896, Florence, also known as the Queen of Happiness, is one of Harlow Ophelia’s dearest friends in the series. They met in 1921, during cutthroat auditions for Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s Shuffle Along. Harlow lands in the chorus but as in real life, Florence makes it into the main cast along with the likes of Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker (Baker was too young for the original production but was a part of the original touring company).

Florence appears in the second book in the series Speaking of War which takes place in 1927. She is largely “offstage” because historically she was touring Europe at the time, but we get a lot of her amazing history through fond reminiscences by Harlow and BB Smith, as well as from newspapers like the New York Amsterdam News and the Inter-State Tattler which breathlessly followed her career in the U.S. and across the pond.It was a life and a career that burned bright like that proverbial shooting star. A child star who performed the vaudeville circuit with her sisters (The Mills Sisters) and other groups such as the Panama Four and the Tennessee Ten, Florence was known for her delicate voice, an arresting stage presence, and a gamine appeal.

After decades in vaudeville, Shuffle Along’s groundbreaking, box office smashing run made her a star. The daughter of former slaves was suddenly in great demand in and out of the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA). Lew Leslie, a white promoter, was one of the people beyond the Negro circuit who sought Florence out. He hired her and her husband Ulysses slow kid Thompson to appear at the segregated Plantation Club. The nightly revue featured a wide range of black artists, including special guests like her old friend Paul Robeson. After a Broadway run, the Plantation Revue headed to Europe in 1922. She performed in English theatrical promoter Charles B. Cochran’s Dover Street to Dixie revue at the London Pavilion. Met with wide acclaim, after England and Paris, Florence returned to New York where in 1924 she headlined the Palace Theater—the most coveted booking in vaudeville. 1926 and Lew Leslie’s Blackbirds brought international fame and a return to the Continent. Among her many fans was the Prince of Wales who is purported to have seen Blackbirds 11 times.

Florence took Europe by storm

Florence’s light touch, her onstage charm was also felt in her everyday life. She was not only popular with the Brits but with her own people. She was considered a role model because not only did she entertain the masses she was an “ambassador of good will. Featured in respected magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair, her signature songs “I’m a Little Blackbird Looking for a Bluebird” and “I’m Cravin’ for that Kind of Love” heard all across the country, Florence was living, breathing, smiling, singing proof that Negroes weren’t the boogeymen that the wider society believed.

From 1922 to 1927 the Queen of Happiness worked continually. No doubt grateful for the opportunities, perhaps fearful of a time when work wasn’t so plentiful, and keenly aware that that time could come again she took what came her way, rarely taking a moments pause. She performed Blackbirds over 300 times in London alone. Sadly, the petite powerhouse’s love of theater and a commitment to the adage “the show must go on” damaged her health. Exhausted, Florence became ill. Major newspapers like the New York Times and the Chicago Defender said complications from appendicitis took the chorine down but others sight tuberculosis. Either way, the pride of Harlem, the pride of her people died on November 1, 1927 in New York City.

Thousands attended her funeral, including famed composer James Weldon Johnson and other stars of the stage, vaudeville, and dance. Singers Ethel Waters and Lottie Gee were among the honorary pallbearers and dignitaries and political figures of both races sent their condolences.

Florence Mills, also known as the Queen of Jazz is credited with fighting for equality, breaking barriers for Negro women in the theater and racial barriers in everyday life. Artists who became exponentially better known like Duke Ellington and Fats Waller wrote songs about her after her death and she even has a building named after her in Sugar Hill, a famous neighborhood in Harlem, yet she is all but forgotten today, rarely remembered outside of theater geeks and African American theater history buffs. But like Aida Overton Walker—another beloved pre-celluloid star—she heavily influenced the style and forbearance of many of the performers who came out of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond. Like the genius of many African American thinkers and performers, Florence Mills was an inverse supernova—a star that suddenly increases greatly in brightness because of a catastrophic explosion that ejects most of its mass. And like starlight, she travels the cosmos in search of believers.

Thousand came to say goodbye to Florence Mills

“Jiggaboos need love too!” or so the song goes. Never heard of it? That’s because the song doesn’t exist outside the world of the Harlow Ophelia Jackson Mystery series. In 1922, this plantation inspired ditty about love among the cotton bolls was a minor novelty hit for BB Smith, the hapless best friend of my main character Harlow Ophelia.

BB is a tough, resourceful woman. Orphaned at a young age, she has made her way in the world with grit, determination and the help of a few good friends like Harlow. But Harlow and the others weren’t always around and sometimes BB didn’t make the best choices. Choices that if she hadn’t gotten her act together prior to 1926 when Speaking Is Easy, the first book in the series, takes place and the Committee on Local Laws reared its ugly mug for the first time, would have landed her on the wrong side of the Committee and the police.

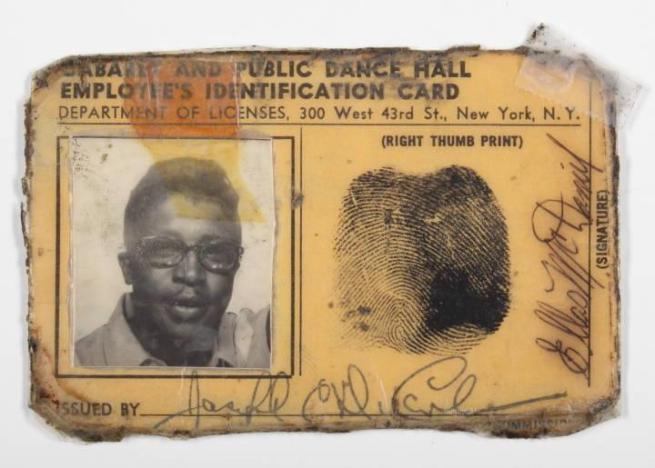

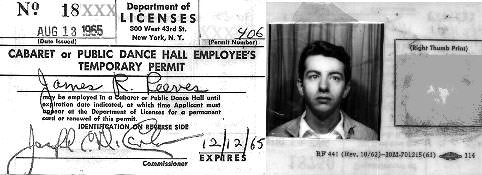

The things Bertha Blossom Smith got up to before settling down would most definitely have gotten her New York City Cabaret License suspended if not outright revoked. That’s if they would have even issued her one after the interrogation!

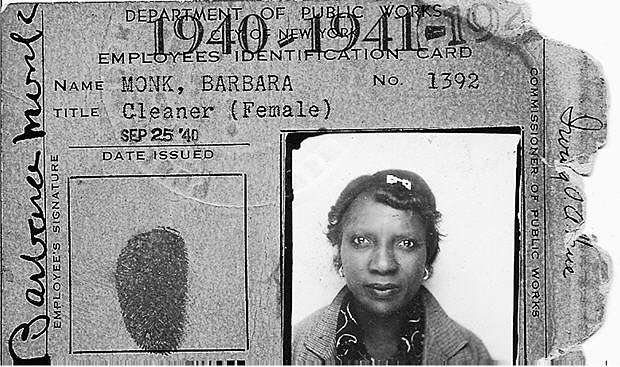

Fingerprinted just to clean the bathroom!

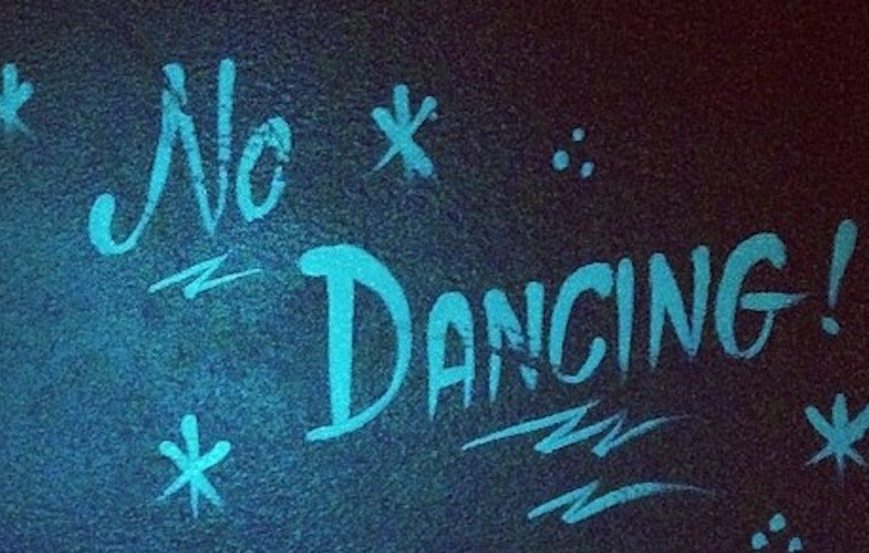

Like “Jiggaboos”, you may never have heard of the Committee on Local Laws or their 1920s era regulation which made it illegal for New York City bars and clubs to host musical entertainment, singing, dancing, or certain other forms of amusement without a license. It also made it illegal for three or more people to dance and in the 1940s expanded its reach to required performers and employees of cabarets to register and carry cabaret cards to perform or work in those already licensed clubs. The license was renewable every two years and entailed a trip to the precinct for an interview, photographing, and fingerprinting just to sing, dance, or play music in a nightclub!

The New York Cabaret License law may not be well known outside of New York or art circles having been overshadowed by Victorian and modern day obscenity fights spear headed by Anthony Comstock, who in 1873 created the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice which entangled the likes of Henry Miller decades later, the 1919 Volstead Act (Prohibition), and The Motion Picture Production Codes (Hays Codes), which William H. Hays created to set industry moral guidelines that were to be applied to motion pictures released by major US studios from 1930 to 1968. Although these other laws had national, far-reaching power, I would argue because of New York’s reputation as an incubator for budding artists and its history of trend-setting and sparking discourse across the country and the world, that NYC’s arbitrary, wrong-headed, and often corrupt cabaret law had nearly as much destructive power as the others. It stalled, cripple, or outright shattered the lives of hundreds if not thousands of artists such as Thelonious Monk and jazz trombonist J.J. Johnson.

Purported to be Bo Diddley

Created six years into Prohibition, which cities like the Big Apple roared passed like a drunk careening through a stop sign, New York’s cabaret laws had been on the books for 91 years until its repeal by Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2017. Like the Volstead Act which was supposed to wipe out licentiousness and alcoholism, the cabaret law was designed to curb the excesses of the roaring twenties. Some also believe because the licensing and the punishment fell so heavily on jazz and blues clubs and therefore Jazz and Blues musicians that it was also seen as a way to stymie race mixing and possible miscegenation, you know excesses.

I imagine the goal of the powers that were, was probably a bit of both. But whatever the reason, the ability to pause or even outright destroy a musician’s career by rejecting their application or either suspending or revoking their cabaret licenses and therefore their opportunity to play in New York clubs, harmed individual performers, music, and music lovers in unfathomable ways.

Performers could be stripped of their card for anything from drug use, to foul language, to debt, to having a criminal record to being scantily clad. The very arbitrariness of the infractions left artists uncertain and fearful of how to proceed. It’s even speculated that it led to the standup comedian and recording artist Lord Buckley’s breakdown and subsequent death and the emotional and financial ruin of the legendary Charlie Parker.

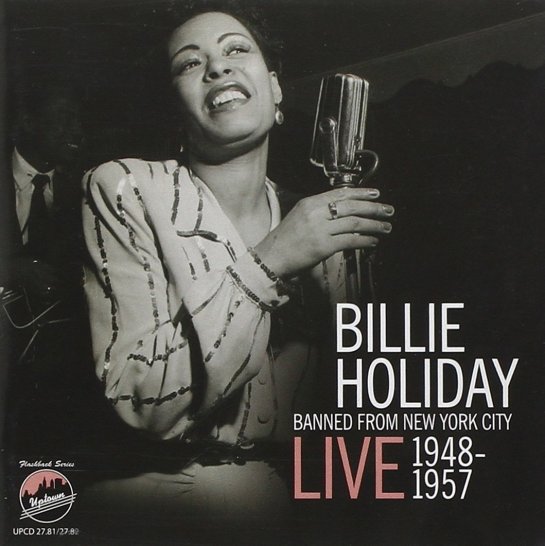

The one and only Lady Day

Like Billie Holiday, one of the most well-known victims of the law (Check out Audra McDonald in Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar and Grill), my BB is just the type of rogue character the laws were designed for. A child prodigy, BB had to put her skills to work after leaving home at the tender age of 16. By the time she landed in NYC in 1919 at age nineteen, she had one divorce, one dead husband, a child, and a raging drug habit. And although she is clean and providing for her kid by the time of the law’s passage, she is still a single mother working out of a nightclub, penning bawdy songs and running numbers.

She’s ripe for the plucking.

Cabaret licenses were designed in part to stop the unknown, the foreign, the lawless, and free, and twentieth-century America didn’t view anything in nature as more unknown, foreign, lawless, or free than the American Negro and that strange thumping, serpentine sound they invented that made one move against one’s own volition. But what was even more dangerous than the American Negro writ large? The Negro woman.

Black men are considered the primary creators of Jazz but this is a false assumption. They may have been the most visible because of sexism, misogyny, and social mores, but men were not the only originators and shapers of America’s only true original art form. There was Mamie Smith, Ethel Waters, and Ma Rainey to name a few who lent a hand, as it were. And although the copper’s dragnet by no means ensnared only Black women—it did punish those deemed to have strayed off the straight and narrow, the most vulnerable, those who couldn’t properly fight back in the courts financially because nightclubs were notoriously stingy, or they simply weren’t given their day in court and a lot of those folks were Black women and men.

Starkly stated, the NYC Cabaret Law, a law that was meant to ensure fire safety, occupancy limits, and the upright moral character of club owners endangered the livelihoods of men and women trying to make a living and provide for their families using their art.

And for those who did and would argue that having to carry a cabaret card wasn’t really that much of a hardship, think of the times. Think through to the real impact, especially on Negro performers. NYC may have been the place to be, but if one couldn’t make a living there, for White artist there were other cities, states, and venues but due to Jim Crow Black artists and other people of color playing “nonwhite” music or too dark to pass, were restricted to a handful of clubs and spaces scattered around the country, which limited exposure, contracts, and the ability to make a name for themselves.

He worked hard for the money

It is well-documented that the original legislation not only banned dancing in unlicensed clubs, but also limited instruments allowed into those clubs to strings, keyboards, and electronic sound systems—leaving out jazz staples like wind, percussion, and brass. It also prohibited more than three musicians from playing at one time—provisions that heavily impacted Harlem jazz clubs and jazz bands. And naturally, law enforcement disproportionally suspended the cab cards of Black musicians because sadly most things don’t change.

People fought back of course but rarely succeeded because most didn’t have the power and clout of Frank Sinatra, who for personal reasons and in an act of solidarity with his fellow artists refused to perform in New York during some of the worst years of the law’s enforcement. Thankfully, Sinatra’s stand eventually helped get the mandatory carrying of the card dropped from the law in 1967.

Book Three of the Harlow Ophelia Jackson Mystery series has yet to be written so BB may still find herself behind the eight ball, but a funny thing that she’s sure to point out if it comes to pass, is that a country which prides itself on its much-ballyhooed belief in Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness has repeatedly deployed draconian rules to hinder the life, liberty, and happiness of its artists.

{Sites used to research this piece}

https://www.local802afm.org/allegro/articles/a-brief-history-of-new-york-citys-cabaret-laws/

https://jazztimes.com/columns/the-gig/the-cabaret-card-and-jazz/

https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/frank-sinatra-billie-holiday-new-yorks-cabaret-law-out

https://thump.vice.com/en_uk/article/z45g5e/nyc-cabaret-law-racism-discrimination-history

ROAR!

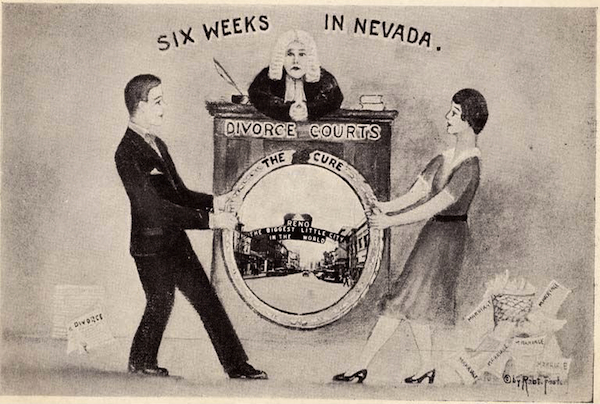

It’s 1926, and you don’t have the green to shoot off to Reno for a not so quickie divorce (It takes at least six weeks or more!) but you still long for freedom. Why not cast your first vote, head over to a Sanger Birth Control Clinic, bob your hair, take up smoking, or buy yourself a Lady Schwinn bicycle to coast around town on?!

What’s this about freedom? Well, although the fight for women’s liberation has been going on from time immemorial and sadly still rages, one of its cherished epochs is August 18, 1920, when the 19th Amendment was ratified, and American women won the right to vote. The vote didn’t change everything of course, but it did, for the first time, empower women’s voices in the public sphere if not the private, giving them a say in how their country was run. What actually helped women’s autonomy in both public and private is war. War?! Yes, war. Because unfortunately, war has often been the engine of both destruction and progress. WWI is no exception.

Louise Brooks

When the US entered the war in 1917, it opened up opportunities for women to join the workforce like never before and join they did, proving in public what they had already known in private: that they were more than capable, intellectually and physically, of taking care of themselves and their families. The sweet taste of freedom that earning one’s own money gives coincided with the advent of modernity. Just as the cotton gin had ushered in a new way of life in the 18th century, women working outside the home in large numbers, the vote, and the automobile heralded a new horizon in the 19th.

Which brings me to the Flapper. In honor of Women’s History Month, I want to talk about Flappers—that most womanly of women and dare I say, the most self-realized of women. Much like the dames of the 1930s and 1940s, no matter how many times men declared it, the Flapper didn’t believe they had to be frumpy to be taken seriously. Seemingly born fully formed from the head of Edwardian sociologist, activist, philosopher Jane Addams and Coco Chanel, the Flapper took the world by storm.

Women chopped their hair, blackened their eyes, and attended petting parties from London to Paris. The term flapper arguably originated in the mountains of Northern England—alternately connoting everything from a teenage girl whose pigtails “flapped” against her back to a woman as a young bird flapping its wings while learning fly, to a young prostitute, before finding its modern definition: an independent, pleasure-loving, free-thinking young woman—but is closely associated with America and women like Zelda Fitzgerald and her fictional counterpart Daisy Buchanan. Which makes sense, because as a very young country which bucked the conventions of the Old World from the get-go, the United States is seen as something of a flapper. So, although one can find Flappers in Mexico and Australia, the Flapper that is most commonly pictured between 1920 and 1929 is a quintessentially American woman.

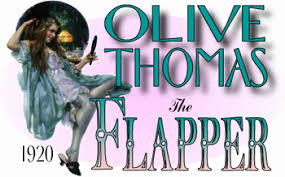

The Flapper, 1920

The end of WWI saw the first flapper movie, 1920’s aptly named The Flapper, and Hollywood “It Girl” Clara Bow breathed life into the celluloid idol, making the Flapper three dimensional across the nation and the world. But the Flapper is not only a powder-pale gal-about-town with a jet black pageboy. No, she comes in other hues, different shades of sepia, cocoa, walnut, and roasted coffee and some might argue, I might argue if one goes with the Roaring Twenties definition—and I do—that those women are the original Flappers.

Black Flappers Holding It Down!

Josephine Baker, The Real “It” Girl

As a feminist who writes novels with badass female characters like my Harlow Ophelia, a Harlem shimmy dancer and part-time sleuth (A Harlow Ophelia Jackson Mystery), I have always loved the 1920s and the Flapper, who to me represents freedom, a wry humor, a sharp intellect, and an unerring fashion sense. Fictional Black women like Harlow and real flesh and blood ones like singer, composer and music critic Nora Holt and the Queen of Happiness cabaret singer, dancer, and comedian Florence Mills paid their rent, kissed who they wanted to kiss, edited magazines, and set the standard of beauty and moxie during the roaring twenties. They, along with Black men, invented the soundtrack and the dance steps of the ’20s. Syncopated Rhythm, anyone? And, honestly, what is more American than the American Negro—a new category of person invented by the Atlantic Slave Trade?

Black women, often the precursors of the next fashion trend as well as the next social upheaval, were never truly eligible for the Cult of Womanhood because one, they have never been perceived as “women”, ie. fragile, respectable, deserving of succor or protection, and two… slavery. When the barbaric practice ended, suddenly free but shut out of decent employment and education, Black men and women had to pool their resources. Women were expected, nay, had to participate in the workforce in order for their families to survive. Black women flapped their wings, their hair, and endured the label of prostitute (which was really just code for ownership of one’s own body) in order to not only be taken seriously but to survive.

The Flapper is synonymous with a good time, but the women who donned low-waisted, knee-length frocks, rouged their cheeks, and danced the Charleston and the Black Bottom until they dropped also worked…hard, as maids, secretaries, cooks, and nannies. Women of color, unlike most white women (willing and unwilling), were historically confined to the home until the 1920s. But women of color worked. They craved freedom, the vote, and a good paying job because they understood that it was the only way to save themselves. They eschewed the golden chains of the Cult of Womanhood and worked, got dirty, flapped their wings and flew.

Florence Mills, She invented the Charleston

So, let’s celebrate the Flapper in her many hues and iterations. Though it didn’t happen in her lifetime, and we are still fighting, she is the foretelling of better things to come for women: physical and mental liberation in a beautiful satin dress.

Happy Women’s History Month!

Harlow and David, a couple deeply in love but who, as they solve murders, also struggle with marriage and commitment. Continue reading

All creation should be a labor of love, or why bother, but writing historical fiction, like well-researched and fact-checked nonfiction takes a special dedication. Continue reading